|

|

| ||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

Camp Zachary Taylor

Jefferson County, Kentucky

| Historical Marker | Images | Article | Links |

My grandfather, Rosler C. Gouge, was stationed at Camp Zachary Taylor at the time of the 1920 Census. It is not known how long he was stationed there, but the Camp was closed that year and the land sold off by 1921.

Camp Zachary Taylor first opened in 1917 as a training camp for World War I soldiers.

Famous Soldiers from Camp Zachary Taylor:

F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940) was stationed at Camp Zachary Taylor in March and April, 1918. The character Daisy in The Great Gatsby is from Louisville, and the Seelbach Hotel in Louisville is the site of Tom and Daisy's wedding reception.

General Anthony Clement McAuliffe (1898-1975), best remembered as the general who replied "Nuts!" when a German general demanded his surrender, attended the Field Artillery School at Camp Taylor. (Some say McAuliffe's reply was actually much stronger.) General McAuliffe earned the Distinguished Service Cross, and later commanded Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

Historical marker unveiled in October 2003.

4016 Poplar Level Road, near Mercer Avenue, Louisville.

Marker #2126

Camp Zachary Taylor

(Louisville, 4016 Poplar Level Rd., Jefferson Co.)

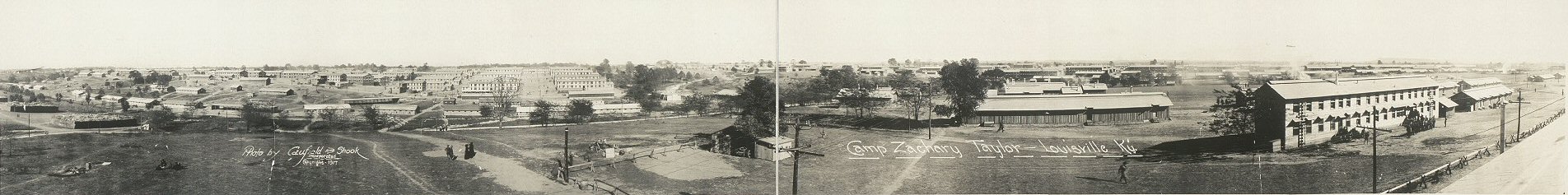

Front: Near this site at Taylor Ave. and Poplar Level Rd. was headquarters of Camp Zachary Taylor. The WW I training camp named for President Zachary Taylor became one of 16 national army camps in the U.S. Begun in June 1917 and built in 90 days on 2,730 acres, the camp contained some 1,700 buildings and housed over 40,000 troops. The first troops arrived in Sept. 1917.

Reverse:

Camp Zachary Taylor

Over 125,000 men were trained here. The 1918 influenza epidemic struck Camp Taylor, killing hundreds of soldiers and hospitalizing thousands of others. By mid-1918 most of the troops were gone. The camp was officially closed in 1920. The land was auctioned off in 1,500 parcels by May 12, 1921. Presented by Stock Yards Bank and Trust Company.

The following images are from P. Darlene McClendon's website. The original images are in the public domain, but the digital images are Copyrighted 2000-2003 by P. Darlene McClendon. You can view more image like these on her site:

Camp Zachary Taylor - Page One Camp Zachary Taylor - Page Two

The following article gives some of the history of Camp Zachary Taylor:

Camp Taylor

The military's influence lived on long after World War I in area's houses, camaraderie

by Grace Schneider

The Courier-Journal, Louisville, Kentucky

http://www.courier-journal.com/reweb/community/placetime/midcounty-camptaylor.html

Champagne corks popped. The Courier-Journal newsroom filled with Louisville's top business leaders, eagerly toasting the biggest news to hit the city in a decade:

Louisville -- on June 11, 1917 -- had been selected by the U. S. War Department as the site for a huge military camp. Camp Zachary Taylor was born shortly after, six miles south of town, on rolling farm land covered with cornstalks, cow pastures, barns and vegetable gardens.

It's hard to picture today, in a time of peace and distaste for the trappings of war, how news of getting a major camp was greeted in Louisville then. Something like a riotous celebration after the University of Louisville wins a basketball championship. Everyone shared the joy, according to newspaper articles in the days after the announcement.

Business people and others saw the announcement for what it was worth -- thousands of dollars in revenue for a city of 235,000.

As time has shown, Camp Taylor forever altered the landscape of the area mostly between what is now Poplar Level Road and Preston Highway. Hastily hammered together, it became the nation's largest military training camp.

After World War I, much of the camp was dismantled. Many of the homes in the area were built with wood from the barracks, stables and other doughboy castoffs -- and were built over the concrete pads that were once used as bathrooms and showers for the camp's barracks.

The modest, mostly wood-frame, one-story homes set the tone for the neighborhood. Today, Camp Taylor is filled with clapboard homes, brick bungalows and many undiscernible former latrines.

Like a lot of young couples, Helen Allgeier Beyerle and her husband Robert patched together a home and a life, starting with their $750 latrine and 120-by-200-foot lot on Clark Street in the early '20s.

"It was nice. It was only six rooms, but I lived in it for 27 years," said Beyerle, 92, the mother of 11 children -- nine born while she lived on Clark Street.

Beyerle now lives on Taylor Avenue, in what was once the heart of the military camp.

She still remembers how people considered the camp site "country" before construction began in the summer of 1917.

The government hired 10,000 carpenters and builders. Because there weren't enough local tradesmen, workers were shipped in by train from places such as Chattanooga, Tenn. Short of housing, Uncle Sam paid to put up the men at the old Galt House at First and Main streets. One day, according to newspaper accounts, 2,000 men carrying tool satchels lined the street waiting to check in.

By late August, a complex big enough to house one-fifth of Louisville's population -- 47,500 men at one time -- had risen, stretching from the present-day grounds of Joe Creason Park southwest to Durrett Lane at Preston Highway.

Some 45.3 million feet of lumber went into building the camp. Total cost: $7.2 million.

Its headquarters were located on what's now the northwest side of the Interstate 264 interchange at Poplar Level Road, the present grounds of Taylor Memorial Park.

A popular boardwalk and amusement area attracted soldiers -- and young women hoping to meet them -- on both sides of Preston Highway near Springdale Avenue. A 53-acre hospital complex sprang up near what's now the Durrett Education Center on Preston.

Lester C. Monk, a 22-year-old farmer from Jersey County, Ill., was the first man to enter the camp. "It was just 9:03 o'clock on that September morning when this young son of democracy became a member of the camp," wrote correspondent Maurice Dunn, in a souvenir booklet printed about the camp.

Local boy John Lee Herbert, of 1717 Payne St., was third.

Their first military meal consisted of sirloin steak with brown gravy, mashed potatoes, stewed tomatoes, peach roll, bread, butter and iced tea.

The inductees, who came from Kentucky, Illinois and Indiana, needed good meals. Some days they woke at 3 or 4 a.m. and marched south on Preston to a rifle range near what is now the Snyder Freeway. Or they dug trenches near what is now the juncture of Crittenden Drive and the Watterson Expressway.

Altogether, more than 125,000 men were trained at Camp Zachary Taylor, "but even more were demobilized and discharged there," according to a 1959 article in The Courier-Journal Magazine. Overwhelmed with 63,000 trainees at one point, the Army erected a tent city in a triangle near what is now Belmar Drive, Preston and the old Southern Railroad tracks.

Disaster struck the 84th -- the name of the division established and stationed there -- in 1918. A flu epidemic put 13,000 men in the hospital and killed 824. People living nearby remembered seeing caskets stacked and tied on trucks leaving the grounds.

Dark days awaited the entire camp after the war ended. The government moved most of its operations to Camp Dix in New Jersey and sent the artillery to what was then called Camp Henry Knox, now Fort Knox.

After serving returning troops, the government chopped the property into parcels and sold it off during the 1920s. The $7 million investment returned $1.1 million.

Some of the soldiers, including Robert Beyerle, bought lots. And a working-class neighborhood, home to bricklayers, carpenters, plumbers and electricians, grew up there during the Depression.

A few tobacco warehouses located in the area, drawing laborers to the community.

Wrote U of L student Margery Plyler in a 1939 English paper on Camp Taylor, on file at the university's archives:

"Living conditions are generally rather poor, but they reach their lowest ebb in what is known as the 'Hospital area' -- so-called because it was here the war-camp hospital was located.

"This is supposedly where the prostitutes and hangers-on of the Camp settled at the close of the War. Here one sees an odd collection of tumble-down shacks where the only seemingly good feature is that the inhabitants are able to get plenty of fresh air."

"It was a poor neighborhood then," said Bob Vogelsburg, of Sylvan Way, who was born and raised in Camp Taylor and remembers hearing stories of the post-camp era.

Most people left school early for factory jobs or a trade, Vogelsburg, 57, said.

The community, annexed by Louisville in 1950, was close-knit, thanks to large families who settled, married among each other and stayed.

"Everybody seemed to have some other relative there," said Betty Horton, of KY 61 in Bullitt County, who organizes an annual reunion for people who grew up in Camp Taylor.

People remember good, simple times. For Horton's husband, Barney, it was sitting outside Catherine Allgeier's kitchen on "baking day" when the mouth-watering, yeasty smell of fresh bread wafted through Warren Street.

Allgeier, the mother of 12, including Fourth Ward Alderman Cyril Allgeier, would hand hot slices slathered with homemade butter out the door to a waiting throng, Betty Horton said.

Some faces have changed, Vogelsburg said, but "the community looks the same as it did when I was a kid."

And many of the old names, like Allgeier and Beyerle, are still there.

"The children," he said, "and the grandchildren stay."

DID YOU KNOW:

F. Scott Fitzgerald was stationed at Camp Taylor and mentions it in his novel "The Great Gatsby." The character Daisy Fay is from Louisville. Nearly 2,000 foreign-born draftees took the oath under a tree on Lee Street. The so-called Naturalization tree was cut to a stump more than 20 years ago. Wooden sewer lines served the camp, and later the community. Many people believe some of the lines are still used, but that's not true. Pipes were shoved through the lines by the late 1930s. Although parts of barracks buildings that were converted into homes are difficult to recognize now, many homes with two chimneys, at opposite ends of a structure, are converted barracks latrines. The camp contained 2,090 buildings, including 114 officers' quarters, 399 enlisted men's barracks, 284 stables and 12 hay sheds.

More Camp Zachary Taylor Links: